After the founding of his association, Mein Grundeinkommen (My Basic Income), which has provided over 650 people with a guaranteed income for a year, Michael Bohmeyer made a surprising observation: the unconditional payment seems to be more important than the amount of money itself. He believes this may be the key to solving the major crises of our time.

Never before has the world faced so many significant challenges all at once. Digitalisation is transforming our economy as profoundly as industrialisation once did, but at a much faster pace. It’s calling into question the foundations of our social systems and the very purpose of human existence. The internet is not only exposing old divisions in society, but also creating new ones. While we’re more connected than ever, we increasingly lack a common vocabulary. This is the breeding ground for populist movements. And as if that weren’t enough, there’s the overarching question: will humanity be able to survive in a world that we ourselves have destroyed?

The overwhelming challenges of the future

The growing complexity of the world is leaving more and more people feeling powerless. Psychologists refer to this as "learned helplessness"—the belief that one has lost the ability to control their life. his feeling of lost control is often accompanied by a sense of personal responsibility for the situation. Over time, this helplessness can lead to depression, a condition whose prevalence continues to rise in affluent societies.

Right now, we need a clear head to get to the root of the major crises. But even though humanity has never had such widespread access to resources and shared knowledge, we’re sinking into a collective prosperity-induced depression. Why?

To understand this, we need to examine how stress affects both individuals and society. The complex, fast-paced, crisis-ridden world places us in a constant state of stress. Although we live in a prosperous country, we operate in a kind of survival mode: will I still be able to live the way I want tomorrow? Will I be able to work, go on vacation, shop, drive, or have children? And do I even have any control over the answers to these questions? While short-term stress helps us ward off dangerous situations and achieve peak performance, long-term stress holds us back. The decisions we make under stress are often short-term, and they don’t fundamentally address our fears: “I’ll try even harder so I don’t lose my job”; “I’ll fly far away on vacation, ignore or deny social problems, buy expensive things, or have parties just to cheer myself up.” These coping mechanisms of avoidance, denial, or escapism don’t address the underlying fear of being unable to shape our own lives. On the contrary, they reinforce the dependency on things continuing as they are – and thus the perceived stress.

How to break the vicious cycle of stress

So how do we break this vicious cycle? Is it by easing the fears of layoffs and unemployment by bailing out destabilised banks and corporations? Should we curb compulsive consumption by morally condemning it? Political measures almost always focus on mitigating the reactions to stress through sanctions, prohibitions, and incentives, rather than addressing the root of the stress itself. However, because the underlying causes—the conscious and unconscious fear of survival—remain unaddressed, new and often more harmful compensatory behaviours continue to emerge.

We therefore need an entirely new political strategy. We must address the root causes and break the vicious cycle of stress.

Our basic income experiment over the past six years has sparked hope. Over 650 people received €1,000 per month of an unconditional basic income for one year. Among them were people from all walks of life: from homeless individuals to millionaires, from members of the Christian Social Union to the Left Party, from students to pensioners. All of them repeatedly reported a similar experience: the security offered by a basic income unlocked new energy. While the recipients often still worked, learned, or got more involved, their perceived stress decreased. It was replaced by a sense of self-efficacy–the belief that they could influence and shape their own lives. With the unconditional security of a basic income, people had the opportunity to examine their existential fears and reflect on them. Do I really want to work so hard at this job? What lies beneath my desire for a luxury item or a long-distance trip? What do I truly want? They took a creative and courageous approach to managing their lives, which in turn led to newfound confidence. Recipients also described this experience as a cycle—a positive one—that continued for years after the basic income ende.

What matters most is the ability to make our own decisions

The money itself seems to be of secondary importance. In many cases, the recipients haven’t spent it at all, or have only spent part of it. It was the unconditional payment that led to the change. It was perceived as an advance in trust, a transfer of responsibility. If an anonymous group pays me money every month without asking for anything in return, it’s up to me to use it meaningfully.

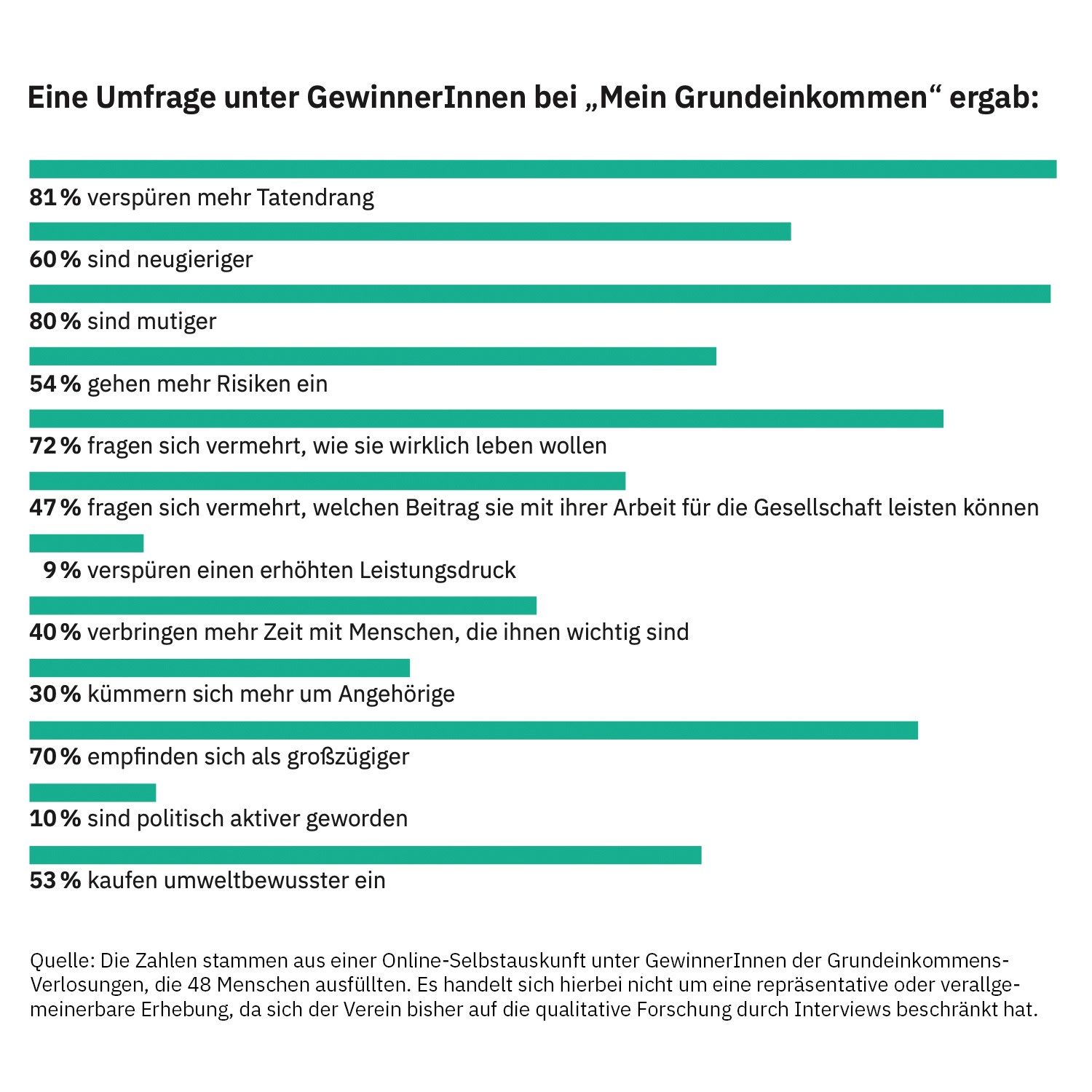

Source: The figures are taken from an online self-disclosure among winners of the basic income lottery, which 48 people completed. This is not a representative or generalisable survey, as the association has so far limited itself to qualitative research through interviews.

After six years and hundreds of stories, we can conclude: people have embraced this responsibility well. They've grown from it and become more resilient.

It is precisely these mature, self-determined, empathetic, self-aware, and responsible individuals that we need to solve the world’s major crises. Since circumstances shape behaviour, it is the responsibility of politics to create conditions that allow everyone the opportunity to develop in this way. We simply need clear heads to tackle digitalisation, the climate crisis, and populism.

Could a basic income help people become more resilient and foster a more resilient society? Could it provide the support for self-help necessary to address humanity’s great challenges? We don’t know, but we’d like to find out.